1. Introduction

In this Green Paper we shall provide an overview of the history of the theology of faith, hope, and love, with specific emphasis on their reception as virtues. As we shall see, the history of these terms has seen marked differences in the way in which each of the three has been understood; the understanding of concept of virtue itself; the understanding of what agency consists in; and the level of involvement of the agent in the acquisition and exercise of the three.

In what follows we shall focus on a number major figures in the history of theology, at times using them as points of departure to discuss the context in which their thinking emerged. We shall begin by discussing the locus classicus of faith, hope, and love within the theological tradition: St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. By examining Paul’s letter, we shall identify a number of questions with which to focus our discussion of St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, and Paul Tillich.

2: Saint Paul

Faith, hope, and love appear together in the distinctive triadic formulation in chapter 13 of St. Paul’s first letter to Corinthians. This is not the only place in which Paul speaks of faith, hope, and love within the same passage; the three are also drawn together in 1 Thessalonians (1:3, 5:7-8)[1] and Galatians (5:4-6)[2]. However, it is the letter to the Corinthians that Paul gives them the most attention. At no point does Paul refer to faith, hope, and love as virtues, let alone theological virtues. Indeed, as we shall see it took until the 13th Century for this term to appear. However, he does draw a distinction between following the law and ‘faith active in love’ (Gal 5:6). Only the latter is ‘in the domain of God’s grace’ (Gal 5:4). Thus, we find in Paul’s letters something resembling the later distinction between deontology and virtue ethics, as well as the grains of Luther’s insistence on the radical distance between law and grace, even if only in nascent form. Rather than describing faith, hope and love as virtues, Paul uses the very broad term pneumatika—‘spiritual things’—to describe the three. In order to understand what Paul has in mind when referring to them as such, we need to look to the context in which they are drawn together in the first place, namely, as part of Paul’s efforts to resolve a number of disputes causing disquiet within the burgeoning church in Corinth, in the establishment of which he had been key.

In Chapter 12 of 1 Corinthians, Paul answers two questions of particular relevance to faith, hope, and love.[3] The first is the theological question of the relative value of each of the spiritual things. Paul delineates three categories of pneumatika: gifts (charismata), services (diakoniai), and works (energemata) and his list of examples of pneumatika is broad.[4] Pneumatika include, but are not restricted to, the utterance of wisdom, the utterance of knowledge, faith, gifts of healing, the working of mighty deeds, prophesy, the discernment of spirits, speaking in tongues, and the interpretation of tongues. Pneumatika are, then, abilities and actions that are inspired by the Spirit. Since there are different categories of pneumatika and many different examples of pneumatika within each category, a question naturally arises as to their relative value. Is the interpretation of tongues of more worth than the utterance of wisdom; is a gift of healing to be valued to a lesser degree than the work of prophesy? The members of the Church in Corinth were involved precisely this kind of dispute.[5]

This theological debate was also, however, a political matter. Since not everyone exhibited the same pneumatika, the question of the hierarchy of the spiritual things was also a question of the hierarchy of the members of the church. Paul responds to both problems with arguments that attempt to settle the theological question of the relative value of the pneumatika while stabilising the political order in the constitution of the Church.

Firstly, Paul argues that since all the pneumatika derive from the same source—and since this source is the one Spirit—there is no question of a conflict between them. The will of the Spirit cannot be disunited, so the acts brought about by that will, though diverse in kind, cannot be of the sort to come into conflict. Thus, the differences of value between pneumatika should not lead to antagonism between the members of the Church; such disputes have a strictly human explanation. While Paul thus reminds the Corinthians that the spiritual things are all of them works of God, his argument leaves unanswered the question of the relative value of the spiritual things. Even supposing that there is no possibility of conflict between the pneumatika, since they are all expressions of God’s will, how should we understand their relative value?

Where Paul’s first argument identified the same Spirit as the common source of the pneumatika, a second argument identifies a common end. According to Paul, to be part of the Church is to be called out to be a participating member in the Body of Christ.[6] Since the Church is the Body of Christ, each of the pneumatika should be considered as a good whose value is derivative of its function within that body. Thus, there is no question of conflict between the pneumatika, not only because they originate from the same source, but also because they are all aimed at the same end: the good of the Body of Christ. Since the good of each member of the Church is the good of the Body of Christ, the achievements of any one member is as much a good for any other member as it is for the achiever; they are all for the good of building up the Church (1 Cor: 12:25-26).

By describing the Church as the Body of Christ, however, Paul is also able to address the relative hierarchy of the various pneumatika. Just as we might think that the heart is more vital to the good of the body than a short hair on a left eyebrow without thinking that there is a conflict between the two, so too while there is a hierarchy of persons within the Church there is no question of there being a conflict between them, since they are all oriented towards the same good (1 Cor 12:27-8).

Thus, Paul’s intervention is an attempt to unify the Church while affirming its hierarchical structure, so as to draw an end to the antagonisms of the Corinthian Church while allowing for differences in value between the different pneumatika exhibited by various members of the Church.[7] He does this by clarifying doctrinal issues with respect to the nature of the Church and the origin and end of the pneumatika.

In Chapter 13, however, Paul complicates the matter further. For although he encourages the members of the Church to aspire to prophesy—since this is a more vital feature of the Body of Christ than, say, the speaking of tongues—he claims that there is, besides the pneumatika already described, ‘a more excellent way’, namely: love (agape). This is a further complication, since Paul’s description of love leaves a number of questions unanswered and which the theological tradition that follows him attempts to answer. In this paper we shall focus on just three of the questions that are raised by Paul’s presentation of love.

The first two questions have to do with the precise relationship between love and the other spiritual things. It is not clear how to read Paul on this issue. On the one hand, love is referred to as one of the charismata—spiritual gifts—a term that Paul uses to describe a category of pneumatika, as we have already seen. This would make it seem that love is of the same order as the other spiritual things, albeit at the top of the hierarchy. On the other hand, however, Paul plainly wishes to distinguish love from other spiritual things in at least one quite fundamental way.[8] Paul states that without love none of the other spiritual things are of any worth: indeed, absent of love they are ‘as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal’. Thus, love cannot be of the same order as the other pneumatika, sitting atop a continuous scale of value. This is because love makes the pneumatika valuable in the first place. Since love bestows value on the pneumatika, it cannot be of the same order of those spiritual things that are made valuable by love. The question of the relationship between love and the other pneumatika is difficult, then, because love is identified as a charismaton and so it seems a sort of pneumatikon, but love is distinguished from the other spiritual things in at least one fundamental respect: since it is that which gives value to the other spiritual things, it cannot be of the same order of value as those spiritual things. What, then, is the relationship between love and the rest of human life such that the former bestows value on the latter?

Paul’s letter also leaves it unclear how we should understand the relationship between love, on the one hand, and faith and hope, on the other. Having described the ways in which love is different from the other spiritual things, Paul draws a special connection between faith, hope, and love. However, Paul states that love is nonetheless the highest. According to Paul, then, there is something of a double-tiered hierarchy among the pneumatika. Firstly, there are those spiritual things which, though differing in value, are all expressions of God’s will and aim at serving the health of the Body of Christ, that is: The Church. However, of the pneumatika there are three of particular significance: faith, hope, and love. But internal to the triad of faith, hope, and love, love is given special prominence: love is the ‘highest’. But what is the relationship between love, on the one hand, and faith and hope, on the other, such that the three are appropriately distinguished from the rest of the pneumatika and such that love is nonetheless the highest of the three?

Clearly, there is much more that could be said about Paul’s presentation of faith, hope, and love. But from what we have seen so far, we have drawn out two questions concerning the nature of the three which we can use in what follows to focus our investigation of the reception of faith, hope, and love in the post-Pauline tradition. Firstly, how are we to understand the distinction between love and the rest of human life, such that the former bestows value on the latter? Secondly, how are we to understand the relationship between the triad, such that, firstly, the three are appropriately distinguished from the rest of the pneumatika and, secondly, that love is nonetheless the highest of the three?

As well as these two, the fact that Paul at no point refers to faith, hope, and love as virtues raises the possibility that they should not properly be considered as such. As we have seen, he clearly identifies one of the distinguishing features of Christian life in contrast to the obedience of the law. But while this is reminiscent of the distinction between deontology and virtue ethics, it is far from isomorphic to it. It is far from clear that the ‘faith active in love’ that is characteristic of Christian life should be considered a matter of virtue, specifically, especially considering that virtues (as understood in contemporary virtue theory, at least) are often considered to be excellent dispositions of character that have their source in the agent’s praiseworthy action. Indeed, as we shall see, the debates over to how to understand the source of value for the distinctive features of Christian life was a major fault line in theological discussions over the following centuries. While Aquinas, for instance, was happy with the language of virtue, for reformists such as Luther, such language was altogether repulsive. Indeed, Luther is said to have described Aristotle—one of the most important influences on Aquinas’s use of virtue theory—as ‘that buffoon who has misled the church’ (quoted in MacIntyre (1998), p. 78). Are, then faith, hope and love virtues at all?

In summary, then, our brief presentation of Paul’s letters has raised three questions which we shall use to interrogate some of the major figures in the history of theology. Firstly, what is the relationship between love and the rest of human life, such that the former bestows value on the latter? Secondly, what is the distinctive relationship between love, on the one hand, and faith and hope on the other? And thirdly, are faith, hope, and love really virtues at all? To begin with, we shall turn to Saint Augustine, whose Enchiridion on Faith, Hope, and Love (‘Enchiridion’ hereafter) proved exceptionally influential in the early-medieval period.

Section Summary:

- Paul draws together faith, hope, and love in several places. The three receive the most treatment in 1 Corinthians 13

- Love is said to be more excellent than the other pneumatika (spiritual things). But faith and hope are drawn into special connection with love.

- Paul’s presentation leaves a number of questions unanswered. Principally, we shall focus on the following three:

- What is the relationship between love and the rest of human life, such that the former bestows value on the latter?

- What is the distinctive relationship between love, on the one hand, and faith and hope on the other?

- Are faith, hope, and love really virtues at all?

3: Saint Augustine

In the centuries following Paul’s letters, Christian thinkers began to take up questions of virtue in a pastoral context, in which the primary concern was to identify and encourage those traits of character which would serve as helpful correctives against sin. Those working in this tradition drew both on Christian scripture, as well as the contemporary understanding of virtue, inherited from the writings of Roman ethicists, such as Seneca and Cicero. Perhaps the two most influential of these theologians were John Cassian and Pope Gregory the great, for both of whom ‘the most urgent challenge of the Christian life is to identify and eliminate the vices which lead to sin’ (Porter, (2001) p.100). Since Cassian and Gregory’s interest with the virtues lay primarily in pastoral care and so in a form of practice, in their writings we find little theoretical development of either the nature of virtue or a systematic understanding of the relationship between the specifically Christian life and the ideal life described by Hellenistic or Roman texts. The first major thinker to address these questions and so to theoretically carve out Christianity’s distinctive understanding of virtue was Saint Augustine. In Augustine’s writings, we can find material for detailed answers for each of the questions identified at the end of the previous section. Let us start with the first question: how does Augustine explain love’s bestowal of value on human life?

Unlike most people who have never described temperance, fortitude, justice and prudence as ‘splendid vices’ (vitia splendida), Augustine is famous for never having done so; while this phrase is often attributed to him, it has become a commonplace in Augustine scholarship to point out that it appears nowhere in his writing. That fact notwithstanding, the phrase contains something of the spirit of Augustine’s position, for by Augustine’s lights the Roman virtues were really nothing other than vices in disguise. Indeed, what is required to raise the merely human into a condition of virtue is the reorientation of human life towards the proper love of God, which orientation is effected by God’s grace. It is in this way that Augustine elaborates on Paul’s claim that love bestows value on human life: for Augustine, it is indeed the case that absent of love all things are as a sounding brass, for without the proper, loving orientation towards God, human life can only be vicious.

In order to understand Augustine’s position, we need to understand the conception of virtue that is at play behind it. This presents an immediate exegetical problem, since within Augustine’s writings there are at least four different definitions of virtue: virtue as perfect reason; virtue as perfect love; virtue as good will; and virtue as rightly-ordered love.[9] However, since our focus shall be on Augustine’s Enchiridion, we shall restrict ourselves to the conception of virtue most closely contemporaneous with that text, namely: virtue as rightly-ordered love. In City of God, during the composition of which the Enchiridion was also completed, Augustine articulates his understanding of this conception of virtue in the following terms:

We must, in fact, observe the right order even in our love for the very love with which we love what is deserving of love, so that there may be in us the virtue which is the condition of the good life. Hence, as it seems to me, a brief and true definition of virtue is ‘rightly ordered love’. (Augustine (2003) p.637)

Virtue, then, is rightly-ordered love.[10] But how is love rightly ordered? Love is rightly-ordered, Augustine elaborates, when one ‘neither loves what he ought not, nor fails to love what he should’ (quoted in Torchia, p.13). For love to be rightly-ordered, then, is for it to take its proper object. But what is love’s proper object? Augustine holds that love takes its proper object when we use (uti) what we should use and enjoy (frui) what we should enjoy (ibid.). If we are to understand how Augustine understands rightly-ordered love, then, we need to understand the distinction between use and enjoyment.

Augustine lays out the distinction precisely in his De doctrina Christiana as follows:

To enjoy [frui] something is to hold fast to it in love for its own sake. To use [uti] something is to apply whatever it may be to the purpose of obtaining what you love—if indeed it is something that ought to be loved. (The improper use of something should be termed abuse.) (quoted in Cahall, p.118)

Thus, to enjoy something is to love it for its own sake and to use something is to relate to it in service of one’s enjoyment of that which should be loved for its own sake. This distinction is normatively laden, however, in the sense that Augustine holds that there are strict limits on what one should enjoy and, therefore, what one should use: ‘It is only the eternal and unchangeable things . . . that are to be enjoyed; other things are to be used so that we may attain the full enjoyment of those things’ (ibid.); ‘The things which are to be enjoyed, then, are the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, and the Trinity that consists of them, which is a kind of single, supreme thing, shared by all who enjoy it’ (quoted in Hubbard, p.206). In summary, then, God is the only proper object of enjoyment; since God is the eternal and unchanging, He is that alone which can be ‘held fast to in love for its own sake’. And since God is the only proper object of enjoyment, all other parts of creation should be used, that is, related to for the sake of the enjoyment of God.

On a natural reading of this distinction—according to which emphasis is placed on using others for the sake of the enjoyment of God—it would seem that enjoyment of God entails using everything else as a mere instrument towards the end of loving God. Torchia appears to endorse this reading and Hannah Arendt outright affirms it (Arendt, p.40). Indeed, on the basis of her reading of the distinction between use and enjoyment as that between means and end, Arendt finds Augustine’s position deeply inimical to the development of a community. It is easy to see why she would have drawn this conclusion. It is certainly not obvious how love can be cultivated between people who think of each other as mere tools to be put to work towards attaining a greater good.

This reading, however, is not uncontroversial; Augustine’s text accepts a more charitable interpretation. In his recent monograph, for instance, Rowan Williams (2016) argues that Augustine’s aim is not to endorse the instrumentalisation of all people and things but, rather, to show how the proper ordering of love undercuts two distinctly human tendencies. The first is to treat objects of love as absolute sources of value. The second is to treat objects of love as being for the sake of the fulfilment of one’s own desires. On Williams’ reading, Augustine’s distinction between use and enjoyment in fact explains how it is possible to first come to love another as both independent of one’s projects and concerns and as a mortal, contingent creature.

That this was Augustine’s intention, Williams argues, is clear from his discussion of his grief over losing his friend, as described in Book IV of his Confessions. In the immediate aftermath of his friend’s death, Augustine tells us that he found solace and joy in the company of friends with whom he shared common interests and pleasures, such that he found himself consoled through being ‘made one’ with his friends:

All kinds of things rejoiced my soul in their company—to talk and laugh and do each other kindnesses; read pleasant books together, pass from lightest jesting to talk of the deepest things and back again; differ without rancour, as a man might differ with himself, and when most rarely dissension arose find our normal agreement all the sweeter for it; teach each other or learn from each other; be impatient for the return of the absent, and welcome them with joy on their homecoming; these and such like things, proceeding from our hearts as we gave affection and received it back, and shown by face, by voice, by the eyes, and a thousand other pleasing ways, kindled a flame which fused our very souls and made us one. (Augustine (1993) p.57)

But the fact that he overcame the pain of loss by throwing himself wholeheartedly into new friendships suggests to Augustine that all he desired from friendship was an expansion of himself through identification with the group. Indeed, the passage above is replete with language of union and identification; Augustine holds that friendship allowed him to experience joy through bonds of recognised familiarity, so much so that that the loss of his friend was experienced as a loss of himself:

This is what men value in friends, and value so much that their conscience judges them guilty if they do not meet friendship with friendship, expecting nothing from their friend save such evidences of his affection. This is the root of the grief when a friend dies, and the blackness of our sorrow, and the steeping of the heart in tears for the joy that has turned to bitterness, and the feeling as though we were dead because he is dead. (op cit. p.58)

In other words, Augustine describes the comfort he took from friends as an effort to replace a lost part of himself with a new prosthetic.

But how is it that by loving God for its own sake we are able to love others as independent of our concerns? One possible answer is that love of God makes possible neighbourly love. As we have seen, Augustine holds that absent of love of God, friendship is a problematic form of extended self-love, since in friendship one takes pleasure from activities in which one might identify with others who share one’s interests. On this understanding, we value others as friends only insofar as they are sufficiently like us to be identified with in friendship. However, since Augustine also holds that God’s love for us is entirely gracious, in the sense that there is nothing we can do to deserve God’s love, if we are loveable to God we are so because he loves us: we are loveable in light of God’s love, not because of the particular characteristics we display[11]. In loving others in light of God’s love, then, we would love them not in virtue of their distinguishing features or qualities, since none of these draws God’s love from Him, but rather in virtue of their being loveable to God. This form of neighbourly love—in which one loves another in respect of their relation to God, which relation holds equally between God and all those whom He loves—is a way of loving another independently of their relation to our personal concerns, since their ability to meet our needs and desires is irrelevant to God’s love for them. In this way, one might argue, neighbourly love, made possible by love of God, frees one to love others as existing independently of one’s concerns. Nonetheless, there remains a profound tension between the neighbourly love made possible by love of God and the sort of preferential love that is characteristic of friendship.

This reading, however, might seem to run contrary to Augustine’s own description of the way in which love of God heals our grief:

Blessed is the man that loves Thee, O God, and his friend in Thee, and his enemy for Thee. For he alone loses no one that is dear to him, if all are dear in God, who is never lost. (ibid.)

That is to say, if you love your friend in God and love your enemy for God, you are blessed since you will never lose those who you love. Here, it seems, Augustine is claiming that in order to guard against the possibility of grief, we need to guard against the possibility of loss. To this end, we need a more durable bond to the object of our affection, which love of God provides. On this reading, God provides relationships of natural love with a guarantee that they cannot be broken.

This reading is problematic, however. As we have seen, Augustine criticises those relationships of natural love that are, in essence, forms of extended self-love. It is difficult to see how such relationships could be any less self-regarding through being made more permanently bonded. Indeed, if this was what Augustine had in mind, the problem would in fact be worse. If God provides a kind of permanent adhesion between the lover and his reflection in the beloved, it would seem that God’s love would in fact make it impossible for us to love another as anything other than our own reflection. Moreover, if Augustine was suggesting that we should love God in order to guard against loss, he would be claiming that love of God is instrumental to our own ends, which is precisely to reverse the use/enjoyment order of privilege that is definitive of rightly-ordered love. Augustine, then, cannot mean that God provides a sort divine superglue to the bond of friendship, such that those who are dear to us in friendship are never lost. What else could he mean?

There is a way of reconciling Augustine’s concern to protect against loss with the possibility that neighbourly love frees us from loving others only as magnifying reflections of ourselves. If I love those who are dear to God, and if all are dear to God, then I love them as my neighbour, since I love them as God loves them, that is, without preference with respect to their individual characteristics. And qua neighbour, I cannot lose the other qua object of natural love, since I am not loving them as the friend with whom I am unified in terms of mutual interests. If the loss of the friend that leads to grief is the loss of a relationship of identification between two people on the basis on shared interests and so on, then I am secured of the possibility of loss not through stronger chemical bonds. Rather, I cannot lose them in that way since the mode of my love for them is not based on valuing them as another me. Through loving them in God, I am not loving the other as another part of myself, so it would be impossible for me to lose them as another part of myself. None of this is, of course, decisive, but hopefully these reflections allow us to see some way of reconciling Augustine’s criticism of friendship on the grounds of its being another form of self-love and his claim that love in God frees us from the possibility of losing the other. On the reading I have just sketched, we are secured against loss not through increasing the strength of the bonds, but rather by being freed to love other in a way that is not dependent on mutable relations.[12]

According to Williams’ reading of Augustine, love of God also undercuts our tendency to treat the other as an absolute source of meaning and value and so to love them as such is to love them as other than they are, since they are contingent and mortal.[13] Williams offers the following explanation:

The question which prompts his formulation [that one should love others for the sake of love of God] is whether a human being is appropriately loved in the mode of ‘enjoyment’, that is, as an end in itself; and his answer, with appropriate qualification, is that this would be to treat another human individual as independently promising final bliss to me, signalling nothing beyond itself. This would be to make the other human being something different from – indeed, something less than – what it in fact is. Each human subject is both res and signum, both a true subsistent reality and a sign of its maker. If I refuse to treat it as a sign of its maker, I take something from its actual ontological complexity and dignity, while at the same time effectively inflating that complexity and dignity to a level it cannot sustain. Only God is to be enjoyed without qualification; only God is a sign of nothing else. (Williams, pp.195-6)

In other words, since only God is an absolute end in itself, to treat another as though she were an absolute end in herself is to burden her with a responsibility that only God can bear. In loving God, we are able to direct our need for security in an absolute end to that which can bear that need. This then frees us to love the other humanly, as the mortal being she is.

According to this more charitable reading of Augustine, then, to use a person ‘for the sake of’ the love of God is to relate to that person humanly, viz., as a mortal, contingent, and independent being that bears the sign of its maker. It is only in this way that one is able to avoid treating the other as a mere instrument to one’s own happiness and without being deceived over the sort of being they truly are.[14]

We are now in a position to offer a fuller statement of Augustine’s understanding of virtue. On Augustine’s account, virtue is well-ordered love. Love is rightly ordered when God (and only God) is enjoyed as the absolute end for all human concern and everything else is used for the sake of that enjoyment. The enjoyment of God frees one to love other people in a manner that is appropriate to their mortal humanity and independence. With this in mind, we can now turn to the contrast Augustine draws between faith, hope, and love, on the one hand, and the Roman virtues on the other.

As we have seen, well-ordered love is love that takes God as the absolute and loves Him accordingly. Well-ordered love, then, depends on faith in God (a point to which we shall return below). If the pagan virtues are conceived without reference to God, the pagan is not capable of well-ordered love, and hence virtue, since she cannot take God as her absolute concern. Any apparent excellences displayed by the pagan, then, will only be merely apparently excellent, since they will not be ordered towards God as the ultimate end. Absent of love of God, were the pagan to take human flourishing as the ultimate end of concern, by Augustine’s lights she would enjoy that which should be merely used (which misuse counts as abuse); in other words, it would be to set up the human good as that which is the ultimate object of human concern, to plant human well-being in place of God.[15] Thus, by Augustine’s concept of virtue, pagan ‘virtues’ can only be vices in disguise.

This is not the whole story, however, for Augustine holds that the Christian conception of virtue allows for the proper understanding of what the Roman virtues are, that is, at their best nothing short of forms of love:

I hold virtue to be nothing else than perfect love of God. For the fourfold division of virtue I regard as taken from four forms of love. For the four virtues… I should have no hesitation in defining them: that temperance is love giving itself entirely to that which is loved; fortitude is love readily bearing all things for the sake of the loved object; justice is love serving only the loved object; prudence is love distinguishing with sagacity between what hinders it and what helps it. (Quoted in Langan, 1978, p.91)

In other words, love of God provides the stable source of value in relation to which the Roman virtues can be properly attuned such that they can, for the first time, come into their own, full maturation by taking their own proper object. It is in this sense that Augustine elaborates on the Pauline claim that love bestows value on the rest of human life. For without love of God, human excellence must fall short of itself by failing to attain its proper end. The Roman virtues only are what they should be when they are forms of love, and this is only possible if one loves God as the absolute end of one’s enjoyment.

We can therefore see Augustine’s answer to our first question. Augustine holds that it is only insofar that we love God for the sake of loving God that our concerns take the proper end. It is through the provision of the proper end to human concern that love is able to properly order human life, and only in this way are we able to attain virtue. Thus, Augustine’s account of the relationship between love and the rest of human life is in line with Paul’s description of love. Love bestows value on all human action and capacity by ordering it towards its proper end; without this ordering, what may appear to be virtuous is in truth as sounding brass, nothing more than a premature and self-aggrandising fanfare.

Does Augustine have an answer to the question of the relationship between faith, hope and love? In order to answer this question, we shall turn to his Enchiridion, since it is there that Augustine offers a detailed account of the relationship between these three.

By Augustine’s analysis, faith, hope, and love are mutually dependent. Thus we can surmise that, for Augustine, the reason that faith and hope are given special prominence over the rest of the spiritual things, is that without them there can be no love. Before we begin to work out how Augustine develops the claim that these three are mutually dependent, we should spend some time briefly discussing Augustine’s understanding of faith and hope.

Faith, Augustine tells us, is belief in things unseen, clearly echoing Paul’s letter to the Hebrews: ‘And what is faith? Faith gives substance to our hopes, and makes us certain of realities we do not see’ (Heb 11:1). By this, Augustine means that faith is assent to the truth of a proposition, which assent is not grounded in empirical facts that one has seen for oneself but, rather, testimony with respect to claims that could not be grounded in empirical knowledge (see Boespflug (2016)).[16] The specific form of religious faith that is under discussion in the Enchiridion, is belief in the Apostle’s Creed, the assent to the truth of which is grounded on the testimony of scripture. Hope is, for Augustine, also propositional and doxastic, in the sense that hope is always with respect to some state of affairs described in a proposition. However, unlike faith, which Augustine claims can be directed towards past, present, or future states of affairs and, moreover, good and bad alike, one can only hope for a future state of affairs that one understands to be good.

Augustine is quite precise in specifying the form of mutual dependency between faith, hope, and love: ‘Wherefore there is no love without hope, no hope without love, and neither love nor hope without faith’ (Augustine (1996) p.9). In other words, love and hope are interdependent and each of this pair is dependent on faith. Augustine is, therefore, committed to the following two claims:

- Love iff hope;

- If either hope or love then faith.

He is not committed to the further claim that faith is dependent on either hope, or love. He offers the following reason for not making this further claim: Demons are just as capable of believing that which is grasped by humans through faith. But while humans hope and love, in light of that belief, the demons fear and tremble.[17] Since faith can be shared by the demonic and the virtuous alike, hope and love cannot be conditions on the possibility of faith. If we are to understand Augustine’s account of the relationship between faith, hope, and love, then, we need to understand his reasons for making the two specific claims regarding their mutual dependency.

We shall begin with the second claim, that love and hope are dependent on faith. As we have seen, Augustine holds that virtue is well-ordered love. Well-ordered love is love that takes God as that, and that alone, which should be enjoyed, such that everything else should be used for the sake of that enjoyment. Moreover, we have seen that Augustine holds that faith is assent to the truth of a proposition. On this account, well-ordered love plainly depends on belief in God such that one can be appropriately directed, in one’s love, towards God. Augustine also holds, however, that human reason is, by itself, incapable of grasping that which would be sufficient for beatitude. Thus, human reason depends on that which is added by faith, the content of which is delivered by sources of scriptural testimony such as the Apostle’s Creed. Well-ordered love is dependent on faith, then, rather than empirical belief, since one requires belief in God in order to take Him as the absolute object of human concern and one cannot attain belief in God by one’s own lights. For similar reasons, Augustine holds that hope is dependent on faith. Since the content of the theologically specific form of hope (namely, in salvation) is provided, again, by sources such as the Creed, hope is dependent on that which allows for the creed to be accepted as true, namely: faith. Thus, the hope in question is the hope for that in which one has faith. Such hope is plainly dependent on faith, since without faith in the Christian doctrine, hope could not take salvation as its object. Thus, love and hope depend on faith.

The more difficult claim to establish is that love and hope are mutually dependent. It is relatively straightforward to argue that hope is dependent on love. We have already seen that Augustine claims that ‘The devils also believe, and tremble’. In other words, while the devils also believe in that future in which the blessed hope, the former tremble. What the devils lack, but the blessed possess, is an apprehension of the future in which one has faith as good. It is the blessed’s love of God that discloses this future as a good to be hoped for, rather than feared. Thus, absent of love there is no hope, since the love of God bestows value on the futures that one believes in.[18]

The most difficult claim to justify is that love is dependent on hope. This is in part down to the paucity of material: Augustine’s only word on the matter in the passage in question is a reference to Paul’s description of ‘faith that worketh by love’ which, Augustine claims, ‘certainly cannot exist without hope’. Augustine’s thought seems to be that the love that is the work of faith is dependent on hope. But this is a more difficult claim to interpret than Augustine lets on. If hope is the hope for one’s own salvation, it is not clear how it is even compatible with well-ordered—that is, God-directed—love, let alone a condition on its possibility.[19] How are we, then, to understand this claim?

We can take a clue in the form of Augustine’s Confessions. The Confessions is not best understood on the model of a contemporary autobiography since, as Rowan Williams argues, the act of recollection that is worked out through the Confessions is also a form of prayer. Williams puts the point as follows:

Book X.vi/9 asks what it is that the writer loves in loving God; and the answer is that it is no kind of sense-impression – though he labours, here and elsewhere, the analogy between the delight of encounter with God and the delights of the senses. God is ‘the life of my soul’s life’; and, as the life of the soul, God must be sought in the soul’s characteristic activity, and so, above all, in the memory – not as a remembered object of perception, but in the remembrance of ‘joy’ or the remembrance of the desire for joy in the truth. (Williams, p.8)

In other words, since God is the life of the soul and the soul’s characteristic activity is recollection, then one loves God precisely through the exercise of that activity in which the soul is most vividly at work. On Williams’ reading, then, Augustine understands the act of recollection to be an exemplary instance of that faith that works through love, since Augustine enacts his faith in God through a devoted act of worship of Him. If an exemplary instance of the working of faith through love is to be found in the very form of recollection as manifest in the Confessions, might this give us a way of understanding how hope is a condition on the possibility of that sort of work?[20]

There is, indeed, a distinctive role for hope in the process of recollection, one to which Augustine is sensitive in his discussion of memory in Book X. Consider the following passage, for instance:

When I turn to memory, I ask it to bring forth what I want: and some things are produced immediately, some take longer as if they had to be brought out from some more secret place in storage; some pour out in a heap, and while we are actually wanting and looking for something quite different, they hurl themselves upon us in masses as though to say “May it not be we that you want?” (Augustine (1993) p.178)

In this passage Augustine is plainly sensitive to the complicated mode of agency involved in recollection. It is not the case that we have control over the memories we are seeking to recover through the process of recollection. Indeed, as Jacob Klein points out in his discussion of Aristotle’s treatise on recollection, recollection begins with the awareness of having forgotten, since it is only because one does not have the memory at the forefront of one’s mind that one has to begin to recollect in the first place.[21] Thus the process of recollection is marked by complicated mode of agency in which the subject ‘asks’ his memory to bring to him the memory he seeks, with the awareness that he cannot attain his goal merely by his own activity.[22]

We need not accept the tight connection Williams draws for Augustine between recollection and worship of God in order to draw a lesson from this discussion. All we need to recover from Williams’ interpretation is the thought that works of love are marked by the agent’s humility with respect to the likelihood of the work’s reaching its end. Hope has an obvious place in any work of love that constitutively requires the agent to recognise that, by her own efforts alone, she is powerless to secure the outcome towards which she is working. This gives us a way of understand why Augustine would think it obvious that the faith that works by love depends on hope: if such works depend for their success on powers beyond one’s control, one can at best only hope that one succeeds.[23]

We are now in a position to summarise Augustine’s answer to our second question. Augustine holds that faith is the assent to a proposition, which assent is based on testimony of scripture, such as the Apostle’s Creed. Just as with faith, hope is assent to the truth of a proposition. Unlike faith, however, we can only hope for future states of affairs that we deem to be good. Augustine explains the relationship between faith, hope, and love in the following terms. Hope and love are interdependent on each other and dependant on faith. Faith makes possible hope and love by allowing love to take its proper object in God and, similarly, in providing content to eschatological hope. Hope is dependent on love, since without love the future state of affairs in which one has faith may just as well be feared; love secures the appearance of the future in which one has faith as good. Finally, love is dependent on hope insofar as love is the working of faith in worship of God through activities which the agent is aware of being unable to achieve by herself.

We are now in a position to turn to the final of our three questions: According to Augustine, are faith, hope, and love virtues? As our previous discussion might suggest, the answer is rather complicated. As we have seen, Augustine holds that love is not a virtue, but virtue itself, and that the so-called virtues (in the plural) are either vices in disguise or otherwise, if properly ordered, nothing other than forms of love. Thus, for Augustine, love is not one virtue among many. Love is virtue, as such, and the human character traits that we might want to describe as virtues are only virtues if they take the form of love. Moreover, as we have seen, faith and hope are conditions on the possibility of love, bestowed by an act of God’s grace. They are not of the same order as the Roman virtues, since they are that by which temperance, fortitude, justice and prudence are reformed into love such that the individual attains virtue.

With this in mind, it is not as surprising as it otherwise might be that in the Enchiridion Augustine never describes faith, hope, and love as virtues: in that text he consistently refers to them as graces, in Pauline fashion. That Augustine describes the three as graces, and not virtues, has both retrospective and prospective import. Firstly, Augustine’s terminology is plainly rooted in Pauline orthodoxy: as we have seen, Paul describes faith, hope, and love as charismata, spiritual gifts. The insistence on faith, hope, and love as graces, then, recalls the scriptural authority of Saint Paul. The language of grace, as opposed to virtue, however, also looks forward to major developments in the theological tradition, for, as we shall see, the distinction between grace and virtue became a major fault line between Scholastic orthodoxy that followed Aquinas and the reformist theology of Luther. For, as we shall see, Luther held that the influence of Aristotle had led to a false emphasis on human achievement and goodness in virtue, which should be corrected by reviving the overwhelming role of God’s grace.

We now draw to a conclusion our discussion of Augustine’s account of faith, hope, and love. In the following section, we shall offer a brief review of the principal theological developments that led to Thomas Aquinas.

Section Summary:

How does Augustine answer our three questions?

- What is the relationship between love and the rest of human life, such that the former bestows value on the latter?

Love bestows value on all human action and capacity by ordering it towards its proper end: enjoyment of God

- What is the distinctive relationship between love, on the one hand, and faith and hope on the other?

Hope and love are interdependent on each other and dependent on faith. Faith makes possible hope and love by allowing love to take its proper object in God and in providing content to hope. Hope is dependent on love, since love secures the appearance of the future in which one has faith as good. Finally, love is dependent on hope insofar as love is the working of faith in worship of God through activities the end of which the agents are self-consciously unable to achieve by their own efforts alone.

- Are faith, hope, and love really virtues at all?

In his ‘Enchiridion’ Augustine never describes faith, hope, and love as ‘virtues’. Rather, they are ‘graces’. He holds that love is virtue, not one among many and, moreover, that either the cardinal virtues are nothing more than vices in disguise or nothing other than forms of love.

4: Saint Thomas Aquinas

a) Aquinas’s Predecessors

In the previous section, we saw that Augustine distinguished between faith, hope, and love, on the one hand, and the Roman virtues, on the other, along the following lines. While the former constitute virtue, and are bestowed by God’s grace, the latter are not really virtues at all unless properly ordered by love. Moreover, when they are properly ordered by love, they are in fact nothing other than aspects or forms of love. Thus, for Augustine, love is virtue. We also noted that the term ‘theological virtues’ appears nowhere in Augustine’s writings. This is hardly a surprise: Given his understanding of virtue as proper love of God, the qualification ‘theological’ is either tautological or misleadingly indicates that there is another sort of virtue, besides that bestowed by God. It is thus understandable that Augustine does not offer a substantial account of the cardinal virtues in their own right, at least nothing comparable to what would come later on, nor develop a systematic account of their relation: in denying that the cardinal virtues are virtues at all, he lacks ground and motivation to work on a systematic presentation of their relation.

During the 12th Century, however, when Christianity was in dominance in Europe and the struggles of early Christianity against Greco-Roman learning were at a safe historical distance, however, theologians began to pay much closer attention to the cardinal virtues in their own right and to develop systematic accounts of their relation to faith, hope, and love.[24] Of these medieval theologians, Thomas Aquinas is perhaps the most obviously associated with the specific notion of the ‘theological virtues’. This is for good reason; Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae is one of the most systematically advanced and influential works of theology of the medieval period and the distinction between theological and cardinal virtues plays a crucial role in that work. But Aquinas’ work is not the origin of the distinction between theological and natural virtues. Aquinas was in fact contributing to a discussion that had been going on for decades. Before we begin to discussion Aquinas’s specific contribution to this discussion, it will help to briefly situate it with relation to his near contemporaries.

In the late 11th Century and into the early 12th Century, medieval theology was beginning to be influenced by what Nederman has called an ‘underground Aristotelianism’, which, prior to the emergence of the Nichomachean Ethics in Latin, drew on Aristotle’s Organon and what fragments of his other writings were transmitted through authors such as Boethius.[25] Theologians did not just restrict their studies in ancient moral thought to Aristotle: interest was revived in the ethical texts of Seneca and Cicero. Consequently, ethics was increasingly considered a discipline in its own right and taught as such in universities:

Ethics had found no place among the seven liberal arts as they were described in the programmes of Boethius, Cassiodore, and Isidore. In the twelfth century attempts were made to find a place for it in systems of teaching. Some writers, such as Honorius of Autun, Stephen of Tournai, and Godfrey of Saint-Victor, freely appended ethics to the end of the list of the seven arts. Hugh of Saint-Victor sandwiched it, as a part of practical philosophy, between logic (grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric) and theoretical philosophy (theology, physics, and mathematics). William of Conches advised that after a student had studied eloquence (grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric) and before he approached theoretical philosophy (the study of corporeal beings in mathematics and physics and of incorporeal beings in theology) he should be instructed in practical philosophy, in ethics, economics, and politics. (Luscombe, xviii)

Within the discipline of ethics, questions naturally emerged as to the proper categorisation of the rather disordered lists of virtues handed down from disparate classical thinkers. Moreover, the renewed attention to classical ethical thought brought theologians up against questions concerning the relation between the teachings of the church fathers and those of the ancient philosophers. During this period, then, work was being done both to systematically organise lists of virtues received from ancient texts and to comprehend the relation between Christian and Pagan teaching.

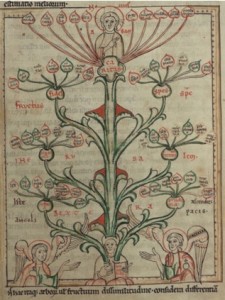

The conceptual distinction required for the theological virtues to be named as a distinctive set within an overarching schema seems to have first appeared in pictorial illustrations of tables of virtues and their corresponding vices, the most prominent of which is attributed to Conrad of Hirsau (ca. 1070 – ca.1150).[26] In Conrad’s illuminations, we find the Roman virtues and faith, hope, and love represented as what Bejczy describes as ‘joint schemes’ (Bejczy, p.121) within an overarching system of ‘principal virtues’. Often, the different virtues are depicted as different branches emerging from the same trunk.

Fig 1.

Thus, we find pictorial representations of Roman virtues as part of a system that includes the theological virtues. The theoretical accounts of virtue that emerged soon after these representations, however, further elaborated the relation between the ‘natural’ and ‘theological’ virtues in different ways. The different directions taken by these elaborations further reflect the disparate origins of medieval moral thought. The two most prominent of these theoretical accounts of virtue are those developed by close contemporaries Peter the Lombard and Peter Abelard. Peter Abelard, following the emergent Aristotelianism, understood virtues as excellences of character, as dispositions towards good action.[27] The Lombard’s main work is the Sentences, a theological text book that brought together teachings of the Church fathers as well as other influences and was a set text in courses of theology at least until the Reformation. In this work, and in contrast to Peter Abelard, the Lombard defined virtue as a quality of the mind that is worked in us by God independently of our own action. Moreover, the Lombard explicitly distinguishes between four categories of virtue:

The virtues fall into four categories, which Peter treats one by one in distinctions 23–36 of book 3: the theological virtues of faith and hope (dist. 23–26), the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance (dist. 33), and the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit (wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of God), which are considered virtues as well (dist. 34–35). A detailed treatise on charity is inserted between the theological and the cardinal virtues, in distinctions 27–32. (Rosemann, p.140)[28]

In summary, by the early 12th century there was a renewed interest in ancient thought; an intellectual climate in which ancient thought is given explicit attention in universities; Christian texts included pictorial representations of faith, hope, and love as comprising a distinct set of virtues within an overarching system of virtue; and there was a live dispute between the two major sources of Christian ethics as to the understanding of virtue, which dispute reflected the pagan and Christian origins of medieval moral thought. It is in this context that we find theologians beginning to systematically relate the two spheres of influence within an overarching schema, thus laying the ground on which it would make sense to distinguish distinctly theological virtues from non-theological virtues.

Of Aquinas’s immediate precursors in the attempt to synthesise the disparate moral traditions, providing solutions to the problems that came with the dispute between the Lombard and Abelard, the two of particular prominence are Albert the Great, Aquinas’s teacher, and William of Auxerre, whose project of systematic theology Albert further extended and developed. Moreover, it is in William’s writings that we find one of the earliest—if not the first—description of theological virtues:

Having spoken of the theological virtues we must now treat of the cardinal virtues [de politicis] before we speak about the gifts of the Holy Spirit (quoted in Cunningham, p.53).

Thus, not only did Aquinas inherit a problematic from an already flourishing tradition of theological thought, he also inherited its terminology. How, though, does Aquinas develop his own answer to the question of the relationship between the cardinal and theological virtues?

b) Aquinas

In order to understand Aquinas’ account of the relationship between the theological virtues and the rest of human life, we need first to understand what he takes to be natural goodness. This will allow us to see how, for him, the naturally attainable virtues of temperance, fortitude, justice, and prudence are insufficient for the attainment of the human good. Since the human good, properly understood, should be conceived as friendship with God, the natural virtues are insufficient for attaining that good. This is the role of the theological virtues, which are but three of the infused virtues, virtues that are bestowed on the human by God.

There are two steps to understanding the outline of Aquinas’s position on the natural goodness of human beings. The first is to understand Aquinas’s general account of goodness, and the second is to see how this is determined in the case of the human good. We shall take each point in turn.

Aquinas finds a tight connection between goodness and being, such that an entity is better or worse according to the degree of its reality.[29] According to Aquinas, in order for an entity to be anything at all, it must be unified in such a way that separates it from other entities. The chair in front of me, for example, is distinct from the table it is pushed underneath and the carpet into which its legs press down. It is distinct from these other entities because it is unified in such a way that excludes the table and the carpet. If it had no constitutive form, by virtue of which it was separate from other entities, the chair would not be anything at all, rather as an iceberg would cease to be if it melted into the ocean.

If, one day in the void, you encountered two chairs emerging from the dark, the chairs would be numerable by virtue of their individual unity and hence distinctness from each other. In order for the chairs to be chairs, as opposed to nothing more than a pair of discrete entities in close proximity, however, Aquinas holds that they must be unified in a way that is characteristic of a kind. In other words, an entity counts as being a particular kind of thing thanks to its having a form of unity that is characteristic of the kind to which it belongs.

According to Aquinas, however, any particular entity can attain the form that is characteristic of its kind to a greater or lesser degree. Consider, for example, a cup of tea into which one continues to pour milk. The drink in front of one will transition from being a cup of tea, through being a milky cup of tea, to being a tea-infused cup of milk. We might think of this transition of the gradual loss of the drink’s distinctive reality as a cup of tea. For in this case, what makes the tea distinctive as a cup of tea is the particular balance of the admixture of tannins and water, which characteristic form of unity is gradually corrupted.

We are now in a position to see why Aquinas finds such a close connection between being and goodness. Consider again our cup of tea. As the encroaching tide of milk begins to overwhelm the infused water, it is not just that the contents of the cup begin to lose their identity as a cup of tea: the drink before us also becomes an increasingly worse cup of tea. To call such a drink a cup of tea would not just be obtuse, it would be an abomination. For, according to Aquinas, the characteristic form of an entity, in virtue of which it is what it is at all, provides a standard according to which any entity counts as a good or bad example of that sort of thing. The degree to which an entity attains in reality the form characteristic of its kind, the closer it approximates the good.[30] Thus, Aquinas finds a very tight connection goodness and being. According to this metaphysics, for a house to be a bad house is for it to be less of a house, since it is less of a realisation of the ideal. And if, to paraphrase A. A. Milne, your house does not look like a house but a tree that has been blown down, it is not just that you have before you a bad house: you no longer have a house at all.

Thus, for Aquinas, for something to be is for it to some degree realise the norms constitutive of the natural kind of which it is an instance. The better something is, the more it is what it is and the converse also holds. What is the ideal form of the human being according to which we are (and are thus better or worse examples of) human beings?

Human beings are living creatures. Aquinas distinguishes living beings from non-living beings on the grounds that the former are capable of moving themselves, rather than being entirely determined by external causes. Since a living being is, by definition, of the sort to be capable of moving itself, it has a distinctive relationship to the good, that is, to the ideal of the kind that is realised to some degree by the creature. This relationship is one of striving, through which living creatures pursue the realisation of the goodness constitutive of their kind. Non-living beings, by contrast, are entirely determined from without as to the degree of their realisation of the ideal of their kind.

A rock, for example, is not itself involved in whether or not it remains a rock, gets smashed to bits under a worker’s hammer, or reduced to magma under the weight of the earth. That it counts as a rock at all is explained entirely by external causation. Living creatures, in contrast, move themselves towards that which sustains their characteristic form of unity, and avoid those things that threaten it. Although living creatures move themselves towards ends that are good for them, however, the ends towards which most living creatures move themselves are determined by natural necessity. A bee, for instance, does not have a range of possible goods to choose between as it leaves the hive for the day: it simply goes about pursuing the things that are set as objects of pursuit by its nature.

Human beings are yet more distinctive still, for while other living creatures are naturally inclined to strive towards those stimuli that draw the creature towards its own good, human beings are capable of free and rational decision. This distinctive feature of human life is of profound importance, since it means that in order for a human being to pursue a course of action, it has to freely choose to pursue that course of action: since the objects of human striving are not set in advance by natural necessity, human beings have to figure out how to act for the best among the available options. Thus, thanks to the lack of natural necessity in the determination of human inclination, in order to strive towards the ends that are truly good for human beings, humans must figure out what ends they are to pursue. The distinctive form of human striving, then, is one in which the human being moves itself towards those stimuli that it judges to be good for it through rational assent. In other words, human striving is characteristically action: behaviour guided by choice constrained by norms of rationality.

In summary, Aquinas held that there was no substantial gap between normativity and being, since for something to be is for it to attain a degree of reality with respect to the ideal of its kind, the fullest degree of such realisation being the good for that being. Living creatures are distinctive in that they strive after their own good, with human beings being still more distinctive insofar the character of their striving is action: behaviour guided by a free, (ideally) rational decision as to what should be done.

With this in mind, we can begin to see the distinctive role Aquinas envisages for the so-called natural virtues of temperance, fortitude, justice, and prudence. In keeping with the ontology of virtue developed over the previous decades, Aquinas held that virtues were dispositions toward correct action.[31] In other words, the virtues are those dispositions that incline the human being towards the sustenance of the form characteristic of the species, namely, behaviour guided by rational choice of ends for action. Thus, the virtues should be considered as those stable dispositions of character that dispose the human individual towards action directed towards its proper end. It is, thus, through proper action (behaviour guided by ideally rational choice) that the human being attains its highest degree of reality that it can achieve by its own efforts and, thereby, attains the highest good it can achieve by its own efforts.

There is much more that can be said about Aquinas’s moral theory. Aquinas has, after all, a detailed account of the role played by each of the moral and intellectual virtues in the attainment of the natural, human good. We have seen enough, however, to begin to see the general shape of the connection between the natural human good and the theological virtues, on Aquinas’s understanding.

So far, then, we have seen in rough outline Aquinas’s account of the natural human good. To attain the natural good, humans must judge the right course of action appropriate to the maintenance of their characteristic form, which course the agent then acts to attain. The natural virtues are those dispositions that dispose the human towards such rationally chosen action. The qualification ‘natural’ is important, however. For, as many scholars of Aquinas are at pains to stress, Aquinas held that the human good as such is not fully specifiable in entirely natural terms.

Jean Porter, for instance, argues that the natural good—attainable through the acquisition of the cardinal virtues through habitual action—is, for Aquinas, only the ‘proximate’ moral aim of human action. This proximate aim of human action is not in itself sufficient for human beings attaining their own good, however, since the distal and true human good is supernatural: beatific vision of and friendship with God. But this vision and friendship is itself only attainable through the presence of the infused virtues, those dispositions towards action characteristic of the life of grace. Thus, the characteristic form of human beings, the attainment of which is the distinctly human good, is not attainable by human action.

Eleonore Stump has taken this insight in a distinctively Augustinian direction. According to Stump, Aquinas held that the natural virtues are not really virtues at all. She points out that Aquinas holds that the natural virtues can be had without the presence of love and that no virtues can be held without love. But ‘this conclusion can be true only if, in his view, the acquired virtues are not real virtues at all’ (Stump (2012) p.95). On this reading, then, Aquinas held with Augustine that the natural virtues are, at best, mere illusions of moral excellence.

Finally, against recent attempts to cash out Aquinas’s moral theory in secular terms, Thomas F. O’Meara has also stressed the essentially theological character of Aquinas’s account of the human good (see O’Meara). On O’Meara’s reading, Aquinas held that ‘nature’ is a category that is parallel but opposed to ‘grace’. Both refer to characteristic forms of unity that are distinctive of human beings. But only grace refers to that specifically spiritual form of human life. Since grace is opposed to nature in terms of its being a distinct form of existence, and since the ‘natural’ form of human existence is not the human good as such, those ‘virtues’ of the natural good should not be thought of as virtues at all, since they do not dispose the agent towards action characteristic of her true—that is, spiritual—good.

These criticisms of the attempt to account for Aquinas’s moral philosophy in entirely human terms are well founded; as Stump in particular argues convincingly, there is a wealth of material in Aquinas’s writings that militates against reading his project as an effort to graft Christian theology onto a framework of pagan ethics, despite a number of prominent readings of Aquinas in this light.[32] Perhaps most telling of all is Aquinas’s most definitive statement of his understanding of virtue, which he attributes to Augustine and affirms in its own right:

A virtue is a good quality of the mind by which one lives righteously, of which no one can make bad use, and which God works in us without us. (ST I-II q. 55, a. 4) [33], [34]

Aquinas could not be clearer: virtue is worked in us, without our own efforts, by God. Thus the natural or acquired ‘virtues’, which are by definition the result of our own habitual action, cannot be considered virtues, properly considered (‘simply’ (simpliciter) without ‘qualification’, as Aquinas puts it elsewhere[35]), since virtue proper is not brought about by our own effort.

Aquinas holds that the distinction between the infused virtues and the natural virtues, then, is radical. What is the nature of the distinction? How is it that love in particular bestows value on the rest of human life?

To begin with, we should examine the distinction Aquinas draws between the infused virtues and the natural virtues. We have already noted that, for Aquinas, the natural virtues are those dispositions towards the best action that can be attained by a human being through her own efforts. The form of life that is shaped by the presence of the four cardinal virtues is the natural or proximate good of the human being: natural, since it is attainable by the agent’s action, and proximate, since it is not the human good as such—the true good for human beings is distal and supernatural. Grace, in contrast, does not name individual, discrete items that are given to individuals by God but, rather, the condition of life in which a graced individual lives, if she has been raised up to virtue by God. It is within this framework that Aquinas characterises the distinction between the natural and infused virtues. The natural virtues are those dispositions towards action that is exemplary of the natural human good, whereas the infused virtues are those dispositions towards action that is exemplary of the supernatural human good, the life of which is grace.[36]

The infused virtues are comprised of four which share a name with the four cardinal virtues—temperance, fortitude, justice, and prudence—as well as the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love. Even though the four moral, infused virtues are homonymous with the natural, cardinal virtues, they comprise a distinct set of virtues. Since virtues are dispositions towards actions, and since actions are identified by reference to the end to which the agent is directed, the identity of a virtue is fixed in part by reference to the end of the action to which that virtue is a disposition. Accordingly, because the infused virtues are by definition dispositions towards ends that are different in kind from the natural virtues, the infused virtues must be distinct from the natural cardinal virtues, despite sharing the same names.[37] Among the infused virtues, however, there is a further distinction to be drawn between the infused or ‘formed’ equivalents to the cardinal virtues and the theological virtues, of which there is no natural equivalent.

Aquinas’s account of the distinction between the natural moral virtues, infused moral virtues, and theological virtues, respectively is, then, quite complex. Happily, Etienne Gilson provides the following helpful summary of the distinction:

There is accordingly a twofold distinction to be made among virtues: first, between theological and moral virtues; second, between natural moral virtues and supernatural moral virtues. Theological virtues and supernatural moral virtues have in common that they are neither acquired nor acquirable by the practice of what is good. As we have said, we cannot naturally practice the good here in question. How could we form a habit of doing something of which we are incapable? On the other hand, the theological virtues are distinguished from the supernatural moral virtues in that the former have God for their immediate object, while the latter bear directly upon certain definite kinds of human acts. Since they pertain to supernatural moral virtues, these acts are directed toward God as to their end. But they are only directed toward him; they do not reach him. The virtue of religion furnishes us with a striking example of this difference. It is in every way a virtue directed toward God. One who possesses this virtue of religion must render to God the worship that is his due, when, where and as it should be rendered. The supernatural moral virtues allow him to act for God; the theological virtues allow him to act with God and in God. By faith we believe God and in God. By hope we entrust ourselves to God and hope in him because he is the very substance of our faith and hope. By charity the act of human love reaches to God himself. We cherish him as a friend whom we love and by whom we are loved, and who through friendship is transported into us and we into him. For my friend I am a friend; hence I am for God what he is for me. (Gilson, 383-4)

In summary, the infused moral virtues are distinguished from the natural moral virtues in terms of the end of the actions towards which the respective sets of virtues dispose the agents. Only the infused moral virtues set the love of God as the end of action. The theological virtues are distinct from the infused moral virtues, however, since the theological virtues take God as the immediate object of action, whereas the actions expressive of the infused moral virtues are only mediately directed towards God. In combination with our brief discussion of grace, we can summarise the point as follows. The infused virtues are those dispositions towards action that is conducive to the attainment of the form of unity that is characteristic of the life of grace, whereas the natural virtues are those dispositions towards action that is conducive to the attainment of the form of unity that is characteristic of the natural life.[38] The theological virtues are infused virtues that take God as the immediate, rather than distal, end, whereas for the other infused virtues it is the converse.

With this framework in place, we can now begin to see how Aquinas conceives of the prominence of love among the virtues, theological and infused. Aquinas explains why love is the highest among the theological virtues along two lines of argument. The first argument picks up on the immediacy of the relation to God that is attained by love, while the second refers to the proper orientation of all action towards its proper end. By the first argument, love is the most excellent since it immediately attains the proper object of virtue (God) to the highest degree:

Since good, in human acts, depends on their being regulated by the due rule, it must needs be that human virtue, which is a principle of good acts, consists in attaining the rule of human acts. Now the rule of human acts is twofold, as stated above (Article 3), namely, human reason and God: yet God is the first rule, whereby, even human reason must be regulated. Consequently the theological virtues, which consist in attaining this first rule, since their object is God, are more excellent than the moral, or the intellectual virtues, which consist in attaining human reason: and it follows that among the theological virtues themselves, the first place belongs to that which attains God most.

Now that which is of itself always ranks before that which is by another. But faith and hope attain God indeed in so far as we derive from Him the knowledge of truth or the acquisition of good, whereas charity attains God Himself that it may rest in Him, but not that something may accrue to us from Him. Hence charity is more excellent than faith or hope, and, consequently, than all the other virtues, just as prudence, which by itself attains reason is more excellent than the other moral virtues, which attain reason in so far as it appoints the mean in human operations or passions.[39]

Faith, hope, and love each take God as their rule, and in this sense attain him. But since faith and hope attain God but only in reference to our own good, they attain God to a lesser degree than love, which rests in God for no other purpose. Thus, love is the highest among the theological virtues.

By the second argument, Aquinas holds that love is that by which the proper end of all action is set, thereby making virtuous action possible in the first place:

If, however, we take virtue as being ordered to some particular end, then we speak of virtue being where there is no charity, in so far as it is directed to some particular good. But if this particular good is not a true, but an apparent good, it is not a true virtue that is ordered to such a good, but a counterfeit virtue. […] If, on the other hand, this particular good be a true good, for instance the welfare of the state, or the like, it will indeed be a true virtue, imperfect, however, unless it be referred to the final and perfect good. Accordingly no strictly true virtue is possible without charity. (ibid.)

Thus, Aquinas, with Augustine, explains the normative distinction between love and the other virtues partly in terms of the orientation towards goodness that love, distinctly, provides. It is for this reason that Aquinas can hold that love is the ‘form’ of the virtues. It is the form of the virtues since it brings them into conformity with the supernatural human good, namely, action towards love of God:

In morals the form of an act is taken chiefly from the end. The reason of this is that the principal of moral acts is the will, whose object and form, so to speak, are the end. Now the form of an act always follows from a form of the agent. Consequently, in morals, that which gives an act its order to the end, must needs give the act its form. Now it is evident, in accordance with what has been said, that it is charity which directs the acts of all other virtues to the last end, and which, consequently, also gives the form to all other acts of virtue: and it is precisely in this sense that charity is called the form of the virtues, for these acts are called virtues in relation to “informed” acts. (ibid.)